Bad Data is a Feature

Incentives create bad data. Better priors are the workaround.

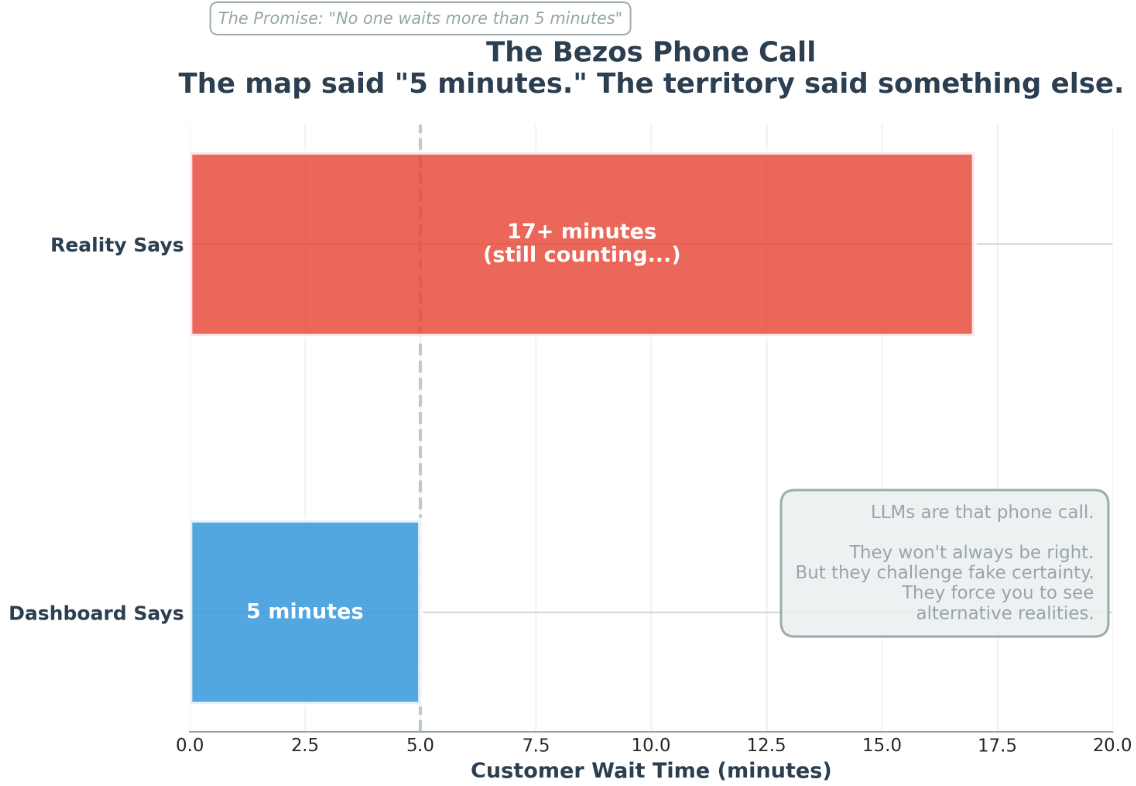

Jeff Bezos once sat in a meeting where the customer-support metrics said:1

“No one waits more than 5 minutes.”

The charts said it.

The dashboards said it.

The managers swore by it.

Bezos said:

“Let’s call them right now.”

5 minutes. 10 minutes. 15 minutes. Still waiting.

The map said “5 minutes.” The territory said “you’re full of it.”

Not an exception.

Green metrics feel safe.

Even as someone obsessed with continuous improvement, I feel safest when nothing looks red.

That’s the real engine behind “bad data”:

When working for truth carries real personal downside and limited upside, people don’t lie — they round. They soften. They blur. They look elsewhere. They drift toward the version of reality that hurts them least.

It’s not malicious. It’s rational.

This is why the “bad data” conversation never dies.

Take telematics.

My insurance company will knock 20% off my premium if I let them track my driving. I want to be a safer driver. I want lower rates. But I still cringe at being monitored.

Do you feel that tension?

Everyone wants the benefits of good data — no one wants the exposure required to produce it.

That same tension lives inside every operation I see.

Executives want insights. Analysts want accuracy. Everyone wants the magic of machine learning.

But machine learning is a dead end with bad data.

And if the production of bad data is incentivized, then good machine learning isn’t just hard — it’s mathematically impossible.

Yes, there are cases where a company invests millions into instrumentation — proper sensors, governance, documentation, everything. ML works great there too.

But more often:

the plan drifted

the sensors were installed by someone who didn’t care

timestamps were typed by a person having a bad day

half the data never got recorded in the first place

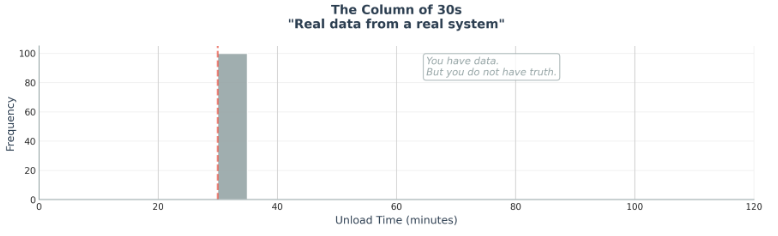

I keep thinking about unload times.

Everyone “has the data.”

And somehow every stop takes exactly 30 minutes.

Every one.

Congratulations.

You have data.

But you don’t have truth.

You have a hallucination — a human one, not an AI one.

And here’s the part no one likes saying out loud: bad data lets everyone pretend everything is fine.

If every unload is “30 minutes,” then nothing is late.

No one needs more staff.

No one blew a deadline.

No one has to explain anything.

Bad data is anesthesia — it keeps the organization comfortably asleep.

And that’s why it persists.

It protects people, not performance.

And here’s the dilemma:

you can’t use ML without reliable variation.

If every unload is stamped “30 minutes,” the algorithm is blind. There’s nothing to learn.

So what then?

What if LLMs could help with this?

You can’t fix incentives overnight. But you can build better priors tomorrow.

The only sane move is to fall back to priors — structural truth instead of recorded “truth.”

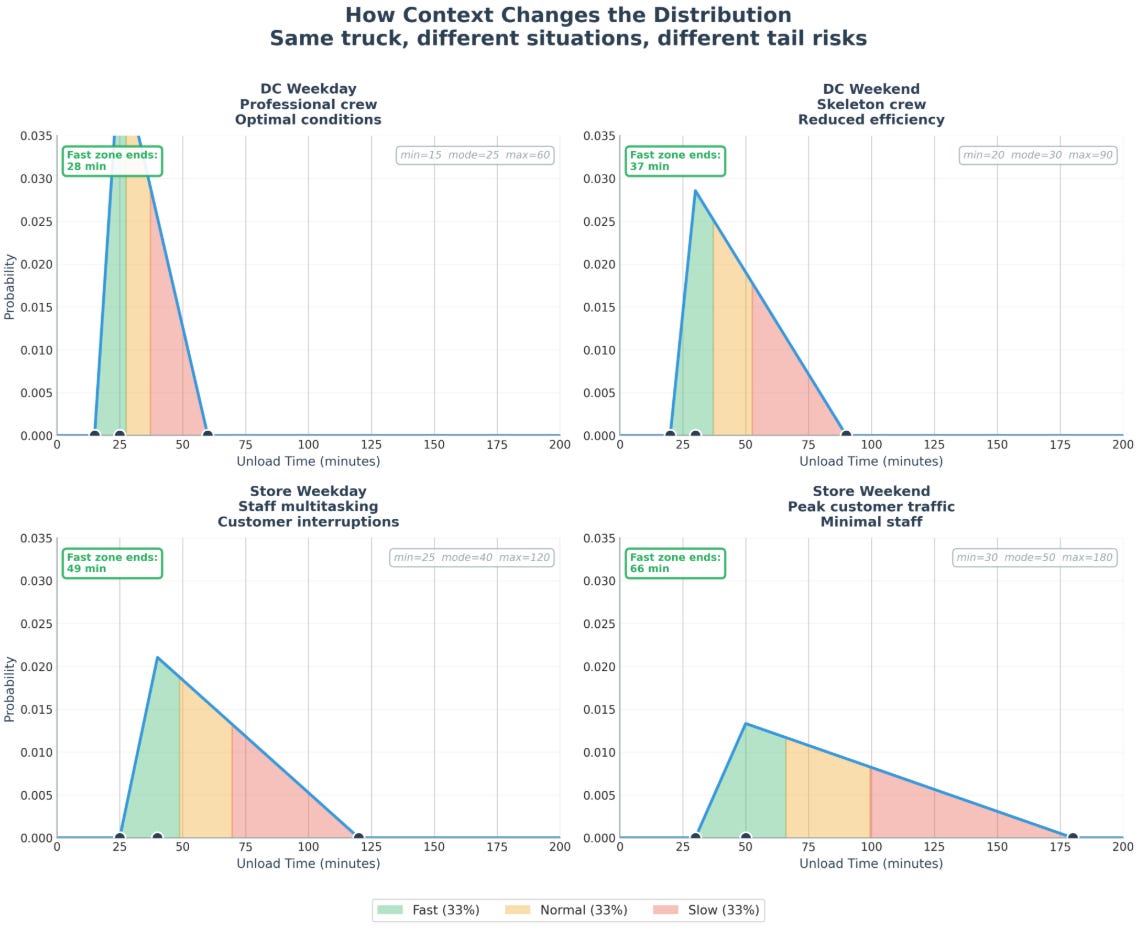

Even when you don’t have clean data, you often know something:

What kind of location is it?

How many pallets?

What type of truck?

Wednesday at a high-volume DC or a lazy Friday afternoon?

These aren’t “ground truth,” but they’re structural truth. Humans use these cues naturally. Experts rely on them instinctively.

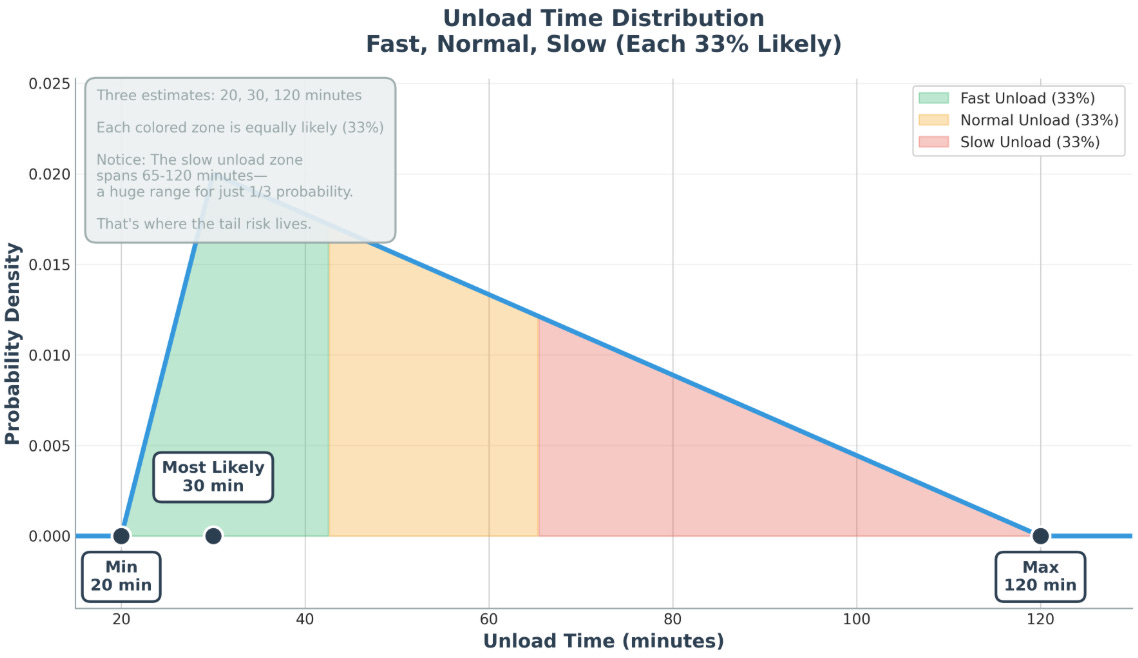

So I tried something:

I asked an LLM:

“Given these conditions, what does unload time usually look like?”

And it gave me a distribution that looked like something an industry veteran would sketch on a napkin:

min ≈ 20

mode ≈ 30

long tail to 120

Not “the truth.” But a plausible truth.

Look at that distribution. Each zone is equally likely; 33% probability.

But the “slow unload” zone? It spans 65 to 120 minutes. That’s a huge range for the same probability as 20 to 43 minutes.

That’s where your tail risk lives. The rare-but-expensive outcomes that blow up your plans.

Want better estimates? Facet by the easily knowable factors.

Want an even better estimate? Feed the LLM research papers. Feed it industry benchmarks. Feed it process descriptions. Each one refines the prior.

It’ll still be wrong. But wrong in the same way a seasoned operator is wrong…

bounded,

structured,

aware of tail risks,

and willing to admit it’s guessing.

This might actually be better than “real” data. Because real data often doesn’t tell you the truth.

LLMs as a Reality Check

Bad data sticks around because it keeps the system stable — predictable in a fake way, comfortable in a dangerous way. LLMs don’t play along with that comfort. They surface possibilities the data is hiding.

Maybe LLMs are that Bezos phone call.

They won’t always be right.

That’s not the point.

The point is they challenge the fake certainty of bad data. They force you to see alternative realities. They illuminate tail risks you didn’t even know existed.

They might save you from your own hallucinations.

Worse Than No Data At All

I’m a data practitioner. I believe in information. I believe in good decision-making. I believe in earning better odds.

But I’ve been burned enough times to know this:

Bad data everyone believes is good data is more dangerous than no data.

And LLMs, for all their flaws, might be a powerful antidote to unearned certainty.

They give us something data-poor-ML can’t: Priors. Distributions. Sketches of the unknown. Structured ignorance. And a way to reason about the world when the data is exactly what we designed it to be: unreliable.

Bezos on Fridman:

"Bad data is anesthesia — it keeps the organization comfortably asleep." -- some good turns id phrase in this one.

I like the telematics example too.